Minoan Civilization on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Minoan civilization was a

The term "Minoan" refers to the mythical King

The term "Minoan" refers to the mythical King

Instead of dating the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of relative

Instead of dating the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of relative

The Minoans were traders, and their cultural contacts reached the

The Minoans were traders, and their cultural contacts reached the  Minoan cultural influence indicates an orbit extending through the Cyclades to Egypt and Cyprus. Fifteenth-centuryBC paintings in

Minoan cultural influence indicates an orbit extending through the Cyclades to Egypt and Cyprus. Fifteenth-centuryBC paintings in

The Minoans raised

The Minoans raised  Cretan cuisine included wild game: Cretans ate wild deer,

Cretan cuisine included wild game: Cretans ate wild deer,

As

As

Apart from the abundant local agriculture, the Minoans were also a

Apart from the abundant local agriculture, the Minoans were also a

Very little is known about the forms of Minoan government; the Minoan language has not yet been deciphered. It used to be believed that the Minoans had a

Very little is known about the forms of Minoan government; the Minoan language has not yet been deciphered. It used to be believed that the Minoans had a

Sheep

Sheep

Men with a special role as priests or priest-kings are identifiable by diagonal bands on their long robes, and carrying over their shoulder a ritual "axe-sceptre" with a rounded blade. The more conventionally-shaped

Men with a special role as priests or priest-kings are identifiable by diagonal bands on their long robes, and carrying over their shoulder a ritual "axe-sceptre" with a rounded blade. The more conventionally-shaped

Haralampos V. Harissis and Anastasios V. Harissis posit a different interpretation of these symbols, saying that they were based on

Haralampos V. Harissis and Anastasios V. Harissis posit a different interpretation of these symbols, saying that they were based on

The handful of very large structures for which Evans' term of

The handful of very large structures for which Evans' term of

For sustaining of the roof, some higher houses, especially the palaces, used columns made usually of ''Cupressus sempervirens'', and sometimes of stone. One of the most notable Minoan contributions to architecture is their inverted column, wider at the top than the base (unlike most Greek columns, which are wider at the bottom to give an impression of height). The columns were made of wood (not stone) and were generally painted red. Mounted on a simple stone base, they were topped with a pillow-like, round

For sustaining of the roof, some higher houses, especially the palaces, used columns made usually of ''Cupressus sempervirens'', and sometimes of stone. One of the most notable Minoan contributions to architecture is their inverted column, wider at the top than the base (unlike most Greek columns, which are wider at the bottom to give an impression of height). The columns were made of wood (not stone) and were generally painted red. Mounted on a simple stone base, they were topped with a pillow-like, round

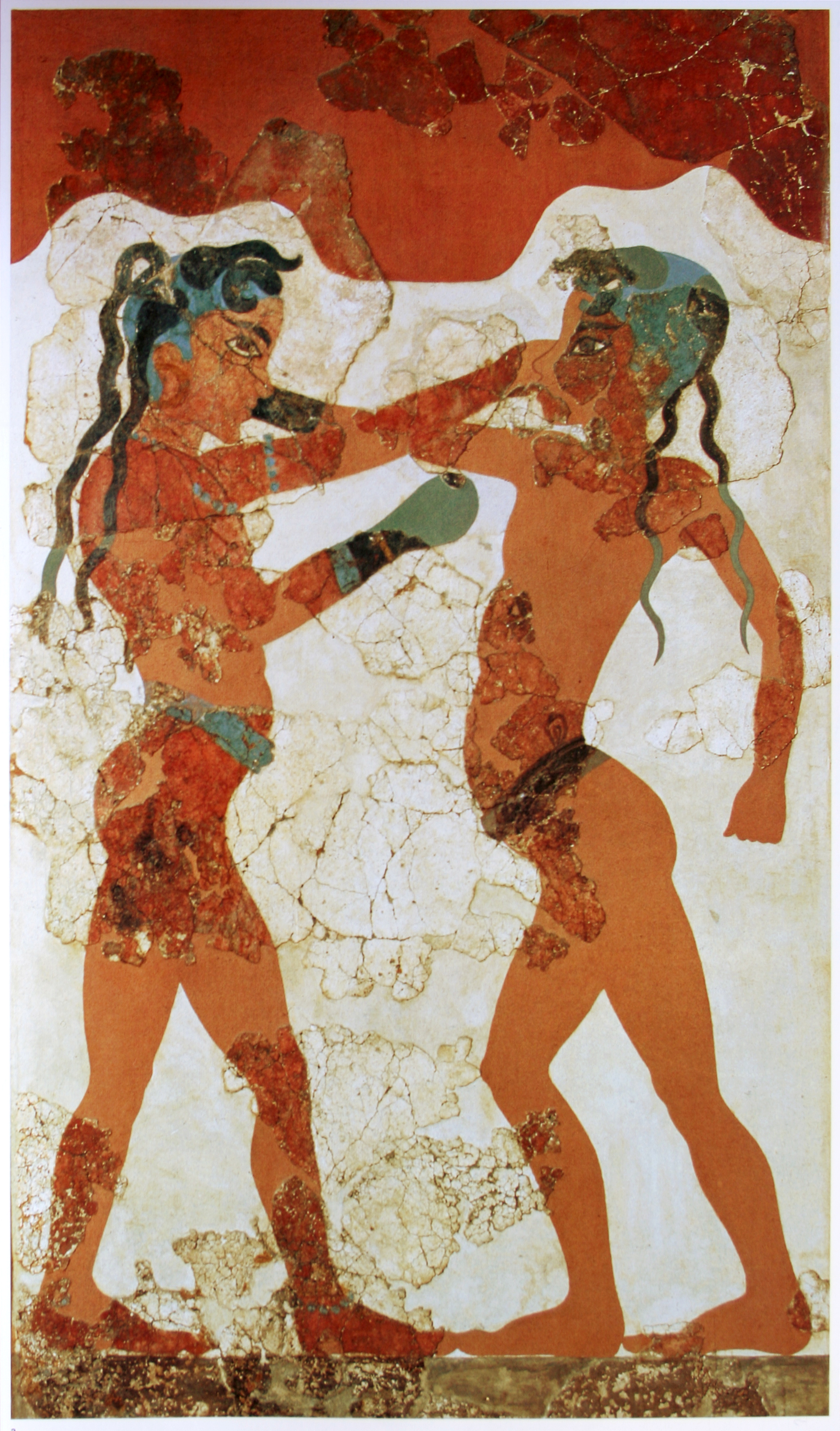

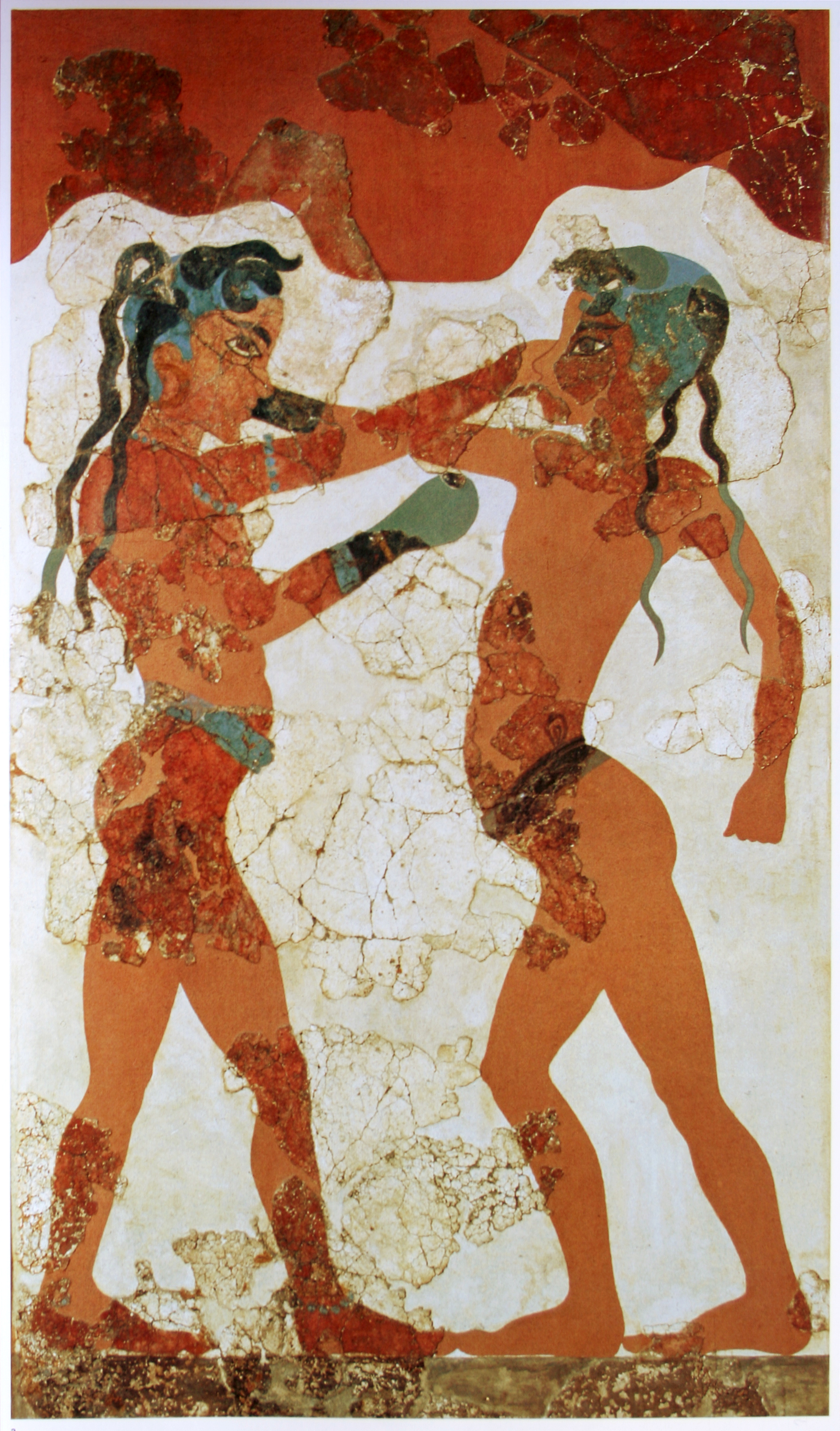

Minoan art has a variety of subject-matter, much of it appearing across different media, although only some styles of pottery include figurative scenes.

Minoan art has a variety of subject-matter, much of it appearing across different media, although only some styles of pottery include figurative scenes.  What is called

What is called

Many different styles of potted wares and techniques of production are observable throughout the history of Crete. Early Minoan ceramics were characterized by patterns of

Many different styles of potted wares and techniques of production are observable throughout the history of Crete. Early Minoan ceramics were characterized by patterns of

Fine decorated bronze weapons have been found in Crete, especially from LM periods, but they are far less prominent than in the remains of warrior-ruled Mycenae, where the famous shaft-grave burials contain many very richly decorated swords and

Fine decorated bronze weapons have been found in Crete, especially from LM periods, but they are far less prominent than in the remains of warrior-ruled Mycenae, where the famous shaft-grave burials contain many very richly decorated swords and

Despite finding ruined watchtowers and fortification walls, Evans said that there was little evidence of ancient Minoan fortifications. According to

Despite finding ruined watchtowers and fortification walls, Evans said that there was little evidence of ancient Minoan fortifications. According to

Between 1935 and 1939, Greek archaeologist

Between 1935 and 1939, Greek archaeologist

google books

* * * * * Dickinson, Oliver (1994; 2005 re-print) ''The Aegean Bronze Age'', Cambridge World Archaeology, Cambridge University Press. * * * *

google books

* Gere, Cathy. ''Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism'',

Modern Antiquarian

*

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

Aegean civilization

Aegean civilization is a general term for the Bronze Age civilizations of Greece around the Aegean Sea. There are three distinct but communicating and interacting geographic regions covered by this term: Crete, the Cyclades and the Greek mainland ...

on the island of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450BC until it ended around 1100BC, during the early Greek Dark Ages

The term Greek Dark Ages refers to the period of Greek history from the end of the Mycenaean palatial civilization, around 1100 BC, to the beginning of the Archaic age, around 750 BC. Archaeological evidence shows a widespread collaps ...

, part of a wider bronze age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near Ea ...

around the Mediterranean. It represents the first advanced civilization in Europe, leaving behind a number of massive building complexes, sophisticated art, and writing systems. Its economy benefited from a network of trade around much of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

.

The civilization was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans

Sir Arthur John Evans (8 July 1851 – 11 July 1941) was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age. He is most famous for unearthing the palace of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete. Based on t ...

. The name "Minoan" derives from the mythical King Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos (; grc-gre, Μίνως, ) was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten ...

and was coined by Evans, who identified the site at Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

with the labyrinth

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth (, ) was an elaborate, confusing structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur, the monster eventually killed by the ...

of the Minotaur

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur ( , ;. grc, ; in Latin as ''Minotaurus'' ) is a mythical creature portrayed during classical antiquity with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "pa ...

. The Minoan civilization has been described as the earliest of its kind in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, and historian Will Durant

William James Durant (; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He became best known for his work '' The Story of Civilization'', which contains 11 volumes and details the history of eastern a ...

called the Minoans "the first link in the European chain".

The Minoans built large and elaborate palaces up to four storeys high, featuring elaborate plumbing systems and decorated with frescoes. The largest Minoan palace is that of Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

, followed by that of Phaistos

Phaistos ( el, Φαιστός, ; Ancient Greek: , , Minoan: PA-I-TO?http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd ), also transliterated as Phaestos, ...

. The function of the palaces, like most aspects of Minoan governance and religion, remains unclear. The Minoan period saw extensive trade by Crete with Aegean and Mediterranean settlements, particularly those in the Near East. Through traders and artists, Minoan cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the Cyclades

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The nam ...

, the Old Kingdom of Egypt

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

, copper-bearing Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

ine coast and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Some of the best Minoan art was preserved in the city of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

; Akrotiri had been effectively destroyed by the Minoan eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean Islands, Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan civilization, Minoan settlement at ...

.

The Minoans primarily wrote in the Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC to write the hypothesized Minoan language or languages. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civil ...

script and also in Cretan hieroglyphs

Cretan hieroglyphs are a hieroglyphic writing system used in early Bronze Age Crete, during the Minoan era. They predate Linear A by about a century, but the two writing systems continued to be used in parallel for most of their history. , they ...

, encoding a language hypothetically labelled Minoan

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450B ...

. The reasons for the slow decline of the Minoan civilization, beginning around 1550BC, are unclear; theories include Mycenaean invasions from mainland Greece

Greece is a country of the Balkans, in Southeastern Europe, bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cretan and the Libyan Seas, an ...

and the major volcanic eruption

Several types of volcanic eruptions—during which lava, tephra (ash, lapilli, volcanic bombs and volcanic blocks), and assorted gases are expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure—have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often ...

of Santorini

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

.

Etymology

The term "Minoan" refers to the mythical King

The term "Minoan" refers to the mythical King Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos (; grc-gre, Μίνως, ) was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten ...

of Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

, a figure in Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

associated with Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describe ...

, the labyrinth

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth (, ) was an elaborate, confusing structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur, the monster eventually killed by the ...

and the Minotaur

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur ( , ;. grc, ; in Latin as ''Minotaurus'' ) is a mythical creature portrayed during classical antiquity with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "pa ...

. It is purely a modern term with a 19th-century origin. It is commonly attributed to the British archaeologist Arthur Evans

Sir Arthur John Evans (8 July 1851 – 11 July 1941) was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age. He is most famous for unearthing the palace of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete. Based on t ...

, who established it as the accepted term in both archaeology and popular usage. But Karl Hoeck had already used the title ''Das Minoische Kreta'' in 1825 for volume two of his ''Kreta''; this appears to be the first known use of the word "Minoan" to mean "ancient Cretan".

Evans probably read Hoeck's book and continued using the term in his writings and findings: "To this early civilization of Crete as a whole I have proposed—and the suggestion has been generally adopted by the archaeologists of this and other countries—to apply the name 'Minoan'." Evans said that he applied it, not invented it.

Hoeck, with no idea that the archaeological Crete had existed, had in mind the Crete of mythology. Although Evans' 1931 claim that the term was "unminted" before he used it was called a "brazen suggestion" by Karadimas and Momigliano, he coined its archaeological meaning.

Chronology and history

Instead of dating the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of relative

Instead of dating the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of relative chronology

Chronology (from Latin ''chronologia'', from Ancient Greek , ''chrónos'', "time"; and , '' -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. I ...

. The first, created by Evans and modified by later archaeologists, is based on pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

styles and imported Egyptian artifacts (which can be correlated with the Egyptian chronology

The majority of Egyptologists agree on the outline and many details of the chronology of Ancient Egypt. This scholarly consensus is the so-called Conventional Egyptian chronology, which places the beginning of the Old Kingdom in the 27th centur ...

). Evans' system divides the Minoan period into three major eras: early (EM), middle (MM) and late (LM). These eras are subdivided—for example, Early Minoan I, II and III (EMI, EMII, EMIII).

Another dating system, proposed by Greek archaeologist Nikolaos Platon

Nikolaos Platon (Greek , Anglicised ''Nicolas Platon''; – ) was a renowned Greek archaeologist. He discovered the Minoan palace of Zakros on Crete.

He put forward one of the two systems of relative Minoan chronology used by archaeologists for ...

, is based on the development of architectural complexes known as "palaces" at Knossos, Phaistos

Phaistos ( el, Φαιστός, ; Ancient Greek: , , Minoan: PA-I-TO?http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd ), also transliterated as Phaestos, ...

, Malia and Zakros Zakros ( el, Ζάκρος; Linear B: zakoro) is a site on the eastern coast of the island of Crete, Greece, containing ruins from the Minoan civilization. The site is often known to archaeologists as Zakro or Kato Zakro. It is believed to have been ...

. Platon divides the Minoan period into pre-, proto-, neo- and post-palatial sub-periods. The relationship between the systems in the table includes approximate calendar dates from Warren and Hankey (1989).

The Minoan eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean Islands, Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan civilization, Minoan settlement at ...

of Thera

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek language, Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English language, English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast ...

occurred during a mature phase of the LM IA period. Efforts to establish the volcanic eruption's date have been controversial. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

has indicated a date in the late 17th centuryBC; this conflicts with estimates by archaeologists, who synchronize the eruption with conventional Egyptian chronology for a date of 1525–1500BC. Tree-ring dating using the patterns of carbon-14 captured in the tree rings from Gordion

Gordion ( Phrygian: ; el, Γόρδιον, translit=Górdion; tr, Gordion or ; la, Gordium) was the capital city of ancient Phrygia. It was located at the site of modern Yassıhüyük, about southwest of Ankara (capital of Turkey), in the ...

and bristlecone pines

The term bristlecone pine covers three species of pine tree (family Pinaceae, genus ''Pinus'', subsection ''Balfourianae''). All three species are long-lived and highly resilient to harsh weather and bad soils. One of the three species, ''Pinus ...

in North America indicate an eruption date around 1560BC.

Overview

Although stone-tool evidence suggests thathominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The t ...

s may have reached Crete as early as 130,000 years ago, evidence for the first anatomically-modern human presence dates to 10,000–12,000 YBP. The oldest evidence of modern human habitation on Crete is pre-ceramic Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

farming-community remains which date to about 7000BC. A comparative study of DNA haplogroups

A haplotype is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent, and a haplogroup ( haploid from the el, ἁπλοῦς, ''haploûs'', "onefold, simple" and en, group) is a group of similar haplotypes that shar ...

of modern Cretan men showed that a male founder group, from Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

or the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, is shared with the Greeks. The Neolithic population lived in open villages. Fishermen's huts were found on the shores, and the fertile Messara Plain

The Messara Plain or simply Messara ( el, Μεσσαρά) is an alluvial plain in southern Crete, stretching about 50 km west-to-east and 7 km north-to-south, making it the largest plain in Crete.

On a hill at its west end are the ruin ...

was used for agriculture.Hermann Bengtson: ''Griechische Geschichte'', C.H. Beck, München, 2002. 9th Edition. . pp. 8–15

Early Minoan

TheBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

began on Crete around 3200BC. The Early Bronze Age (3500 to 2100BC) has been described as indicating a "promise of greatness" in light of later developments on the island. In the late third millenniumBC, several locations on the island developed into centers of commerce and handiwork, enabling the upper classes to exercise leadership and expand their influence. It is possible that the original hierarchies of the local elites were replaced by monarchies, a precondition for the palaces.Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: ''Die Griechische Frühzeit'', C.H. Beck, München, 2002. . pp. 12–18 Pottery typical of the Korakou culture

The Korakou culture or Early Helladic II (in some schemes Early Helladic IIA) was an early phase of Bronze Age Greece, in the Early Helladic period, lasting from around 2650 to c.2200 BC. In the Helladic chronology it was preceded by the Eutres ...

was discovered in Crete from the Early Minoan Period.

Middle Minoan

The Minoan palaces began to be constructed during this period of prosperity and stability, during which the Early Minoan culture turned into a "civilization". At the end of the MMII period (1700BC) there was a large disturbance on Crete—probably an earthquake, but possibly an invasion from Anatolia. The palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Kato Zakros were destroyed. At the beginning of the neopalatial period the population increased again, the palaces were rebuilt on a larger scale and new settlements were built across the island. This period (the 17th and 16th centuriesBC, MM III-Neopalatial) was the apex of Minoan civilization. After around 1700BC,material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects creat ...

on the Greek mainland reached a new high due to Minoan influence.

Late Minoan

Another natural catastrophe occurred around 1600BC, possibly an eruption of the Thera volcano. The Minoans rebuilt the palaces with several major differences in function. Around 1450BC, Minoan culture reached a turning point due to a natural disaster (possibly an earthquake). Although another eruption of the Thera volcano has been linked to this downfall, its dating and implications are disputed. Several important palaces, in locations such as Malia, Tylissos, Phaistos and Hagia Triada, and the living quarters of Knossos were destroyed. The palace in Knossos seems to have remained largely intact, resulting in its dynasty's ability to spread its influence over large parts of Crete until it was overrun by theMycenaean Greeks

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

.

After about a century of partial recovery, most Cretan cities and palaces declined during the 13th centuryBC (LHIIIB-LMIIIB). The last Linear A archives date to LMIIIA, contemporary with LHIIIA. Knossos remained an administrative center until 1200BC. The last Minoan site was the defensive mountain site of Karfi

Karfi (also Karphi, el, Καρφί) is an archaeological site high up in the Dikti Mountains in eastern Crete, Greece. The ancient name of the site is unknown; "Karfi" ("the nail") is a local toponym for the prominent knob of limestone that mar ...

, a refuge which had vestiges of Minoan civilization nearly into the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

.

Foreign influence

The influence of Minoan civilization is seen in Minoan art and artifacts on theGreek mainland

Greece is a country of the Balkans, in Southeastern Europe, bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cretan and the Libyan Seas, an ...

. The shaft tomb

A shaft tomb or shaft grave is a type of deep rectangular burial structure, similar in shape to the much shallower cist grave, containing a floor of pebbles, walls of rubble masonry, and a roof constructed of wooden planks.

Practice

The practi ...

s of Mycenae had several Cretan imports (such as a bull's-head rhyton

A rhyton (plural rhytons or, following the Greek plural, rhyta) is a roughly conical container from which fluids were intended to be drunk or to be poured in some ceremony such as libation, or merely at table. A rhyton is typically formed in t ...

), which suggests a prominent role for Minoan symbolism. Connections between Egypt and Crete are prominent; Minoan ceramics are found in Egyptian cities, and the Minoans imported items (particularly papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

) and architectural and artistic ideas from Egypt. Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

might even have been models for the Cretan hieroglyphs

Cretan hieroglyphs are a hieroglyphic writing system used in early Bronze Age Crete, during the Minoan era. They predate Linear A by about a century, but the two writing systems continued to be used in parallel for most of their history. , they ...

, from which the Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC to write the hypothesized Minoan language or languages. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civil ...

and Linear B

Linear B was a syllabic script used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1400 BC. It is descended from ...

writing systems developed. Archaeologist Hermann Bengtson has also found a Minoan influence in Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ite artifacts.

Minoan palace sites were occupied by the Mycenaeans around 1420–1375BC. Mycenaean Greek

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language, on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BC), before the hypothesised Dorian invasion, often cited as the ''terminus ad quem'' for the ...

, a form of ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

, was written in Linear B, which was an adaptation of Linear A. The Mycenaeans tended to adapt (rather than supplant) Minoan culture, religion and art, continuing the Minoan economic system and bureaucracy.

During LMIIIA (1400–1350BC), ''k-f-t-w'' was listed as one of the "Secret Lands of the North of Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

" at the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III

The Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, also known as Kom el-Hettân, was built by the main architect Amenhotep, son of Hapu, for Pharaoh Amenhotep III during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. The mortuary temple is located on the Western bank ...

. Also mentioned are Cretan cities such as Amnisos, Phaistos, Kydonia and Knossos and toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

s reconstructed as in the Cyclades

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The nam ...

or the Greek mainland. If the values of these Egyptian names are accurate, the Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

did not value LMIII Knossos more than other states in the region.

Geography

Crete is a mountainous island with naturalharbor

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is a ...

s. There are signs of earthquake damage at many Minoan sites, and clear signs of land uplifting and submersion of coastal sites due to tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

processes along its coast.

According to Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Crete had 90 cities.Homer, ''Odyssey'' xix. Judging by the palace sites, the island was probably divided into at least eight political units at the height of the Minoan period. The majority of Minoan sites are found in central and eastern Crete, with few in the western part of the island, especially to the south. There appear to have been four major palaces on the island: Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

, Phaistos

Phaistos ( el, Φαιστός, ; Ancient Greek: , , Minoan: PA-I-TO?http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd ), also transliterated as Phaestos, ...

, Malia, and Kato Zakros Zakros ( el, Ζάκρος; Linear B: zakoro) is a site on the eastern coast of the island of Crete, Greece, containing ruins from the Minoan civilization. The site is often known to archaeologists as Zakro or Kato Zakro. It is believed to have been ...

. At least before a unification under Knossos, north-central Crete is thought to have been governed from Knossos, the south from Phaistos, the central-eastern region from Malia, the eastern tip from Kato Zakros, the west from Kydonia

Kydonia or Cydonia (; grc, Κυδωνία; lat, Cydonia) was an ancient city-state on the northwest coast of the island of Crete. It is at the site of the modern-day Greek city of Chania. In legend Cydonia was founded by King Cydon (), a son ...

. Smaller palaces have been found elsewhere on the island.

Major settlements

*Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

– the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete. Knossos had an estimated population of 1,300 to 2,000 in 2500BC, 18,000 in 2000BC, 20,000 to 100,000 in 1600BC and 30,000 in 1360BC.

* Phaistos

Phaistos ( el, Φαιστός, ; Ancient Greek: , , Minoan: PA-I-TO?http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd ), also transliterated as Phaestos, ...

– the second-largest palatial building on the island, excavated by the Italian school shortly after Knossos

* Malia – the subject of French excavations, a palatial center which provides a look into the proto-palatial period

* Kato Zakros Zakros ( el, Ζάκρος; Linear B: zakoro) is a site on the eastern coast of the island of Crete, Greece, containing ruins from the Minoan civilization. The site is often known to archaeologists as Zakro or Kato Zakro. It is believed to have been ...

– sea-side palatial site excavated by Greek archaeologists in the far east of the island, also known as "Zakro" in archaeological literature

* Galatas – confirmed as a palatial site during the early 1990s

*Kydonia

Kydonia or Cydonia (; grc, Κυδωνία; lat, Cydonia) was an ancient city-state on the northwest coast of the island of Crete. It is at the site of the modern-day Greek city of Chania. In legend Cydonia was founded by King Cydon (), a son ...

(modern Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

), the only palatial site in West Crete

* Hagia Triada – administrative center near Phaistos which has yielded the largest number of Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC to write the hypothesized Minoan language or languages. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civil ...

tablets.

* Gournia

Gournia ( el, Γουρνιά) is the site of a Minoan palace complex on the island of Crete, Greece, excavated in the early 20th century by the American archaeologist, Harriet Boyd-Hawes. The original name for the site is unknown. The modern nam ...

– town site excavated in the first quarter of the 20th century

* Pyrgos – early Minoan site in southern Crete

* Vasiliki – early eastern Minoan site which gives its name to distinctive ceramic ware

* Fournou Korfi – southern site

* Pseira

Pseira ( el, Ψείρα) is an islet in the Gulf of Mirabello in northeastern Crete with the archaeological remains of Minoan and Mycenean civilisation.

History

The island was explored in 1906–1907 by Richard Seager and partially document ...

– island town with ritual sites

* Mount Juktas

A mountain in north-central Crete, Mount Juktas ( el, Γιούχτας - ''Giouchtas''), also spelled Iuktas, Iouktas, or Ioukhtas, was an important religious site for the Minoan civilization. Located a few kilometers from the palaces of Knossos ...

– the greatest Minoan peak sanctuary, associated with the palace of Knossos

* Arkalochori

Arkalochori ( el, Αρκαλοχώρι) is a town and a former municipality in the Heraklion regional unit, Crete, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Minoa Pediada, of which it is a municipal unit. The m ...

– site of the Arkalochori Axe

The Arkalochori Axe is a 2nd millennium BC Minoan bronze votive double axe (''labrys'') excavated by Spyridon Marinatos in 1934 in the Arkalochori cave on Crete, which is believed to have been used for religious rituals. It is inscribed with fifte ...

* Karfi

Karfi (also Karphi, el, Καρφί) is an archaeological site high up in the Dikti Mountains in eastern Crete, Greece. The ancient name of the site is unknown; "Karfi" ("the nail") is a local toponym for the prominent knob of limestone that mar ...

– refuge site, one of the last Minoan sites

* Akrotiri – settlement on the island of Santorini

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

(Thera), near the site of the Thera Eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on near ...

* Zominthos

Zominthos ( el, Ζώμινθος, alternative spellings ''Ζόμινθος'' or ''Ζόμιθος'') is a small plateau in the northern foothills of Mount Ida (Psiloritis), on the island of Crete. Zominthos is roughly 7.5 kilometers west of the vil ...

– mountainous city in the northern foothills of Mount Ida

Beyond Crete

The Minoans were traders, and their cultural contacts reached the

The Minoans were traders, and their cultural contacts reached the Old Kingdom of Egypt

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

, copper-containing Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

and the Levantine coast and Anatolia. In late 2009 Minoan-style frescoes and other artifacts were discovered during excavations of the Canaanite palace at Tel Kabri

Tel Kabri ( he, תֵל כַבְרִי), or Tell al-Qahweh ( ar, تَلْ ألْقَهوَة, , mound of coffee), is an archaeological tell (mound created by accumulation of remains) containing one of the largest Middle Bronze Age (2,100–1,5 ...

, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, leading archaeologists to conclude that the Minoan influence was the on the Canaanite city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

.

Minoan techniques and ceramic styles had varying degrees of influence on Helladic Greece. Along with Santorini, Minoan settlements are found at Kastri, Kythera

Kastri is a village in the island of Cythera, Islands regional unit, Greece. Kastri has been occupied by humans since the Bronze Age, and was an important settlement of the Early Helladic/Minoan Period of Crete. Kastri is thought to have been an ...

, an island near the Greek mainland influenced by the Minoans from the mid-third millenniumBC (EMII) to its Mycenaean occupation in the 13th century. Minoan strata replaced a mainland-derived early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

culture, the earliest Minoan settlement outside Crete.

The Cyclades were in the Minoan cultural orbit and, closer to Crete, the islands of Karpathos

Karpathos ( el, Κάρπαθος, ), also Carpathos, is the second largest of the Greek Dodecanese islands, in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Together with the neighboring smaller Saria Island it forms the municipality of Karpathos, which is part o ...

, Saria and Kasos

Kasos (; el, Κάσος, ), also Casos, is a Greek island municipality in the Dodecanese. It is the southernmost island in the Aegean Sea, and is part of the Karpathos regional unit. The capital of the island is Fri. , its population was 1,22 ...

also contained middle-Bronze Age (MMI-II) Minoan colonies or settlements of Minoan traders. Most were abandoned in LMI, but Karpathos recovered and continued its Minoan culture until the end of the Bronze Age. Other supposed Minoan colonies, such as that hypothesized by Adolf Furtwängler

Johann Michael Adolf Furtwängler (30 June 1853 – 10 October 1907) was a German archaeologist, teacher, art historian and museum director. He was the father of the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler and grandfather of the German archaeologist Andr ...

on Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born ...

, were later dismissed by scholars. However, there was a Minoan colony at Ialysos

Ialysos ( el, Ιαλυσός, before 1976: Τριάντα ''Trianta'') is a town and a former municipality on the island of Rhodes, in the Dodecanese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Rhodes, of which ...

on Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

.

Minoan cultural influence indicates an orbit extending through the Cyclades to Egypt and Cyprus. Fifteenth-centuryBC paintings in

Minoan cultural influence indicates an orbit extending through the Cyclades to Egypt and Cyprus. Fifteenth-centuryBC paintings in Thebes, Egypt

, image = Decorated pillars of the temple at Karnac, Thebes, Egypt. Co Wellcome V0049316.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Pillars of the Great Hypostyle Hall, in ''The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia''

, map_type ...

depict Minoan-appearing individuals bearing gifts. Inscriptions describing them as coming from ''keftiu'' ("islands in the middle of the sea") may refer to gift-bringing merchants or officials from Crete.

Some locations on Crete indicate that the Minoans were an "outward-looking" society. The neo-palatial site of Kato Zakros Zakros ( el, Ζάκρος; Linear B: zakoro) is a site on the eastern coast of the island of Crete, Greece, containing ruins from the Minoan civilization. The site is often known to archaeologists as Zakro or Kato Zakro. It is believed to have been ...

is located within 100 meters of the modern shoreline in a bay. Its large number of workshops and wealth of site materials indicate a possible ''entrepôt

An ''entrepôt'' (; ) or transshipment port is a port, city, or trading post where merchandise may be imported, stored, or traded, usually to be exported again. Such cities often sprang up and such ports and trading posts often developed into co ...

'' for trade. Such activities are seen in artistic representations of the sea, including the ''Ship Procession'' or "Flotilla" fresco in room five of the West House at Akrotiri.

Agriculture and cuisine

The Minoans raised

The Minoans raised cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

, sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

, pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s and goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the a ...

s, and grew wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

, vetch

''Vicia'' is a genus of over 240 species of flowering plants that are part of the legume family (Fabaceae), and which are commonly known as vetches. Member species are native to Europe, North America, South America, Asia and Africa. Some other ...

and chickpea

The chickpea or chick pea (''Cicer arietinum'') is an annual legume of the family Fabaceae, subfamily Faboideae. Its different types are variously known as gram" or Bengal gram, garbanzo or garbanzo bean, or Egyptian pea. Chickpea seeds are high ...

s. They also cultivated grapes, figs

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

and olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ...

s, grew poppies Poppies can refer to:

*Poppy, a flowering plant

*The Poppies (disambiguation) - multiple uses

*''Poppies (film)'' - Children's BBC remembrance animation

*"Poppies", a song by Patti Smith Group from their 1976 album ''Radio Ethiopia''

*"Poppies", th ...

for seed

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiospe ...

and perhaps opium. The Minoans also domesticated bees. Hood, Sinclair (1971) "The Minoans; the story of Bronze Age Crete"

Vegetables, including lettuce

Lettuce (''Lactuca sativa'') is an annual plant of the family Asteraceae. It is most often grown as a leaf vegetable, but sometimes for its stem and seeds. Lettuce is most often used for salads, although it is also seen in other kinds of food, ...

, celery

Celery (''Apium graveolens'') is a marshland plant in the family Apiaceae that has been cultivated as a vegetable since antiquity. Celery has a long fibrous stalk tapering into leaves. Depending on location and cultivar, either its stalks, lea ...

, asparagus

Asparagus, or garden asparagus, folk name sparrow grass, scientific name ''Asparagus officinalis'', is a perennial flowering plant species in the genus ''Asparagus''. Its young shoots are used as a spring vegetable.

It was once classified in ...

and carrot

The carrot ('' Daucus carota'' subsp. ''sativus'') is a root vegetable, typically orange in color, though purple, black, red, white, and yellow cultivars exist, all of which are domesticated forms of the wild carrot, ''Daucus carota'', nat ...

s, grew wild on Crete. Pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in the Northern Hemisphere in late summer into October. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the family Rosaceae, bearing the p ...

, quince

The quince (; ''Cydonia oblonga'') is the sole member of the genus ''Cydonia'' in the Malinae subtribe (which also contains apples and pears, among other fruits) of the Rosaceae family (biology), family. It is a deciduous tree that bears hard ...

, and olive trees were also native. Date palm

''Phoenix dactylifera'', commonly known as date or date palm, is a flowering plant species in the palm family, Arecaceae, cultivated for its edible sweet fruit called dates. The species is widely cultivated across northern Africa, the Middle Eas ...

trees and cats (for hunting) were imported from Egypt. The Minoans adopted pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

s from the Near East, but not lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

s and oranges

An orange is a fruit of various citrus species in the family Rutaceae (see list of plants known as orange); it primarily refers to ''Citrus'' × ''sinensis'', which is also called sweet orange, to distinguish it from the related ''Citrus × ...

.

They may have practiced polyculture

In agriculture, polyculture is the practice of growing more than one crop species in the same space, at the same time. In doing this, polyculture attempts to mimic the diversity of natural ecosystems. Polyculture is the opposite of monoculture, i ...

, and their varied, healthy diet resulted in a population increase. Polyculture theoretically maintains soil fertility and protects against losses due to crop failure. Linear B tablets indicate the importance of orchards (figs

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

, olives and grapes) in processing crops for "secondary products". Olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: f ...

in Cretan or Mediterranean cuisine

Mediterranean cuisine is the food and methods of preparation used by the people of the Mediterranean Basin. The idea of a Mediterranean cuisine originates with the cookery writer Elizabeth David's book, ''A Book of Mediterranean Food'' (1950) ...

is comparable to butter in northern European cuisine. The process of fermenting wine from grapes was probably a factor of the "Palace" economies; wine would have been a trade commodity and an item of domestic consumption. Farmers used wooden plow

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

s, bound with leather to wooden handles and pulled by pairs of donkey

The domestic donkey is a hoofed mammal in the family Equidae, the same family as the horse. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as a ...

s or oxen.

Seafood was also important in Cretan cuisine. The prevalence of edible molluscs

An edible item is any item that is safe for humans to eat. "Edible" is differentiated from "eatable" because it does not indicate how an item tastes, only whether it is fit to be eaten. Nonpoisonous items found in nature – such as some mushroo ...

in site material and artistic representations of marine fish and animals (including the distinctive Marine Style

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning rela ...

pottery, such as the LM IIIC "Octopus" stirrup jar), indicate appreciation and occasional use of fish by the economy. However, scholars believe that these resources were not as significant as grain, olives and animal produce. "Fishing was one of the major activities...but there is as yet no evidence for the way in which they organized their fishing." An intensification of agricultural activity is indicated by the construction of terraces and dams at Pseira in the Late Minoan period.

Cretan cuisine included wild game: Cretans ate wild deer,

Cretan cuisine included wild game: Cretans ate wild deer, wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is ...

and meat from livestock. Wild game is now extinct on Crete. A matter of controversy is whether Minoans made use of the indigenous Cretan megafauna, which are typically thought to have been extinct considerably earlier at 10,000BC. This is in part due to the possible presence of dwarf elephant

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes (around ) in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephants are an example ...

s in contemporary Egyptian art.

Not all plants and flora were purely functional, and arts depict scenes of lily-gathering in green spaces. The fresco known as the ''Sacred Grove'' at Knossos depicts women facing left, flanked by trees. Some scholars have suggested that it is a harvest festival or ceremony to honor the fertility of the soil. Artistic depictions of farming scenes also appear on the Second Palace Period "Harvester Vase" (an egg-shaped rhyton

A rhyton (plural rhytons or, following the Greek plural, rhyta) is a roughly conical container from which fluids were intended to be drunk or to be poured in some ceremony such as libation, or merely at table. A rhyton is typically formed in t ...

) on which 27 men led by another carry bunches of sticks to beat ripe olives from the trees.

The discovery of storage areas in the palace compounds has prompted debate. At the second "palace" at Phaistos, rooms on the west side of the structure have been identified as a storage area. Jars, jugs and vessels have been recovered in the area, indicating the complex's possible role as a re-distribution center for agricultural produce. At larger sites such as Knossos, there is evidence of craft specialization (workshops). The palace at Kato Zakro indicates that workshops were integrated into palace structure. The Minoan palatial system may have developed through economic intensification, where an agricultural surplus could support a population of administrators, craftsmen and religious practitioners. The number of sleeping rooms in the palaces indicates that they could have supported a sizable population which was removed from manual labor.

Tools

Tools, originally made of wood or bone, were bound to handles with leather straps. During theBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, they were made of bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

with wooden handles. Due to its round hole, the tool head would spin on the handle. The Minoans developed oval-shaped holes in their tools to fit oval-shaped handles, which prevented spinning. Tools included double adze

An adze (; alternative spelling: adz) is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing ...

s, double- and single-bladed axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

s, axe-adzes, sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting, or reaping, grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock, ei ...

s and chisel

A chisel is a tool with a characteristically shaped cutting edge (such that wood chisels have lent part of their name to a particular grind) of blade on its end, for carving or cutting a hard material such as wood, stone, or metal by hand, stru ...

s.

Women

As

As Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC to write the hypothesized Minoan language or languages. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civil ...

Minoan writing has not been deciphered yet, most information available about Minoan women is from various art forms and Linear B

Linear B was a syllabic script used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1400 BC. It is descended from ...

tablets, and scholarship about Minoan women remains limited.

Minoan society was a divided society separating men from women in art illustration, clothing, and societal duties. For example, documents written in Linear B have been found documenting Minoan families, wherein spouses and children are not all listed together. In one section, fathers were listed with their sons, while mothers were listed with their daughters in a completely different section apart from the men who lived in the same household, signifying the vast gender divide present in Minoan society.

Artistically, women were portrayed very differently from men. Men were often artistically represented with dark skin while women were represented with lighter skin. Minoan dress representation also clearly marks the difference between men and women. Minoan men were often depicted clad in little clothing while women's bodies, specifically later on, were more covered up. While there is evidence that the structure of women's clothing originated as a mirror to the clothing that men wore, fresco art illustrates how women's clothing evolved to be increasingly elaborate throughout the Minoan era. Throughout the evolution of women's clothing, a strong emphasis was placed on the women's sexual characteristics, particularly the breasts. Female clothing throughout the Minoan era emphasized the breasts by exposing cleavage or even the entire breast. Minoan women were also portrayed with "wasp" waists, similar to the modern bodice women continue to wear today.

Fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

paintings portray three class levels of women; elite women, women of the masses, and servants. A fourth, smaller class of women are also included among some paintings; women who participated in religious and sacred tasks. Elite women were depicted in paintings as having a stature twice the size of women in lower classes, as this was a way of emphasizing the important difference between the elite wealthy women and the rest of the female population within society.

Childcare was a central job for women within Minoan society. Other roles outside the household that have been identified as women's duties are food gathering, food preparation, and household care-taking. Additionally, it has been found that women were represented in the artisan world as ceramic and textile craftswomen. As women got older it can be assumed that their job of taking care of children ended and they transitioned towards household management and job mentoring, teaching younger women the jobs that they themselves participated in.

While women were often portrayed in paintings as caretakers of children, pregnant women were rarely shown in frescoes. Pregnant women were instead represented in the form of sculpted pots with the rounded base of the pots representing the pregnant belly. Additionally, no Minoan art forms portray women giving birth, breast feeding, or procreating. Lack of such actions leads historians to believe that these actions would have been recognized by Minoan society to be either sacred or inappropriate, and kept private within society.

Childbirth was a dangerous process within Minoan society. Archeological sources have found numerous bones of pregnant women, identified by the fetus bones within their skeleton found in the abdomen area, providing strong evidence that death during pregnancy and childbirth were common features within society. Further archeological finds provide evidence for female death caused by nursing as well. Death of this population is attributed to the vast amount of nutrition and fat that women lost because of lactation which they often could not get back.

Society and culture

Apart from the abundant local agriculture, the Minoans were also a

Apart from the abundant local agriculture, the Minoans were also a mercantile

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exchan ...

people who engaged significantly in overseas trade, and at their peak may well have had a dominant position in international trade over much of the Mediterranean. After 1700BC, their culture indicates a high degree of organization. Minoan-manufactured goods suggest a network of trade with mainland Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

(notably Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. Th ...

), Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

and westward as far as the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. Minoan religion

Minoan religion was the religion of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete. In the absence of readable texts from most of the period, modern scholars have reconstructed it almost totally on the basis of archaeological evidence of such as M ...

apparently focused on female deities, with women officiants. While historians and archaeologists have long been skeptical of an outright matriarchy

Matriarchy is a social system in which women hold the primary power positions in roles of authority. In a broader sense it can also extend to moral authority, social privilege and control of property.

While those definitions apply in general E ...

, the predominance of female figures in authoritative roles over male ones seems to indicate that Minoan society was matriarchal, and among the most well-supported examples known.

The term palace economy

A palace economy or redistribution economy is a system of economic organization in which a substantial share of the wealth flows into the control of a centralized administration, the palace, and out from there to the general population. In turn ...

was first used by Evans of Knossos. It is now used as a general term for ancient pre-monetary cultures where much of the economy revolved around the collection of crops and other goods by centralized government or religious institutions (the two tending to go together) for redistribution to the population. This is still accepted as an important part of the Minoan economy; all the palaces have very large amounts of space that seems to have been used for storage of agricultural produce, some remains of which have been excavated after they were buried by disasters. What role, if any, the palaces played in Minoan international trade is unknown, or how this was organized in other ways. The decipherment of Linear A would possibly shed light on this.

Government

Very little is known about the forms of Minoan government; the Minoan language has not yet been deciphered. It used to be believed that the Minoans had a

Very little is known about the forms of Minoan government; the Minoan language has not yet been deciphered. It used to be believed that the Minoans had a monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

supported by a bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

. This might initially have been a number of monarchies, corresponding with the "palaces" around Crete, but later all taken over by Knossos, which was itself later occupied by Mycenaean overlords. But, in notable contrast to contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

n civilizations, "Minoan iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

contains no pictures of recognizable kings", and in recent decades it has come to be thought that before the presumed Mycenaean invasion around 1450BC, a group of elite families, presumably living in the "villas" and the palaces, controlled both government and religion.

Saffron trade

A fresco of saffron-gatherers atSantorini

Santorini ( el, Σαντορίνη, ), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα ) and classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation ), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the ...

is well-known. The Minoan trade in saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of ''Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma and styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly as a seasoning and colouring agent i ...

, the stigma of a naturally-mutated crocus

''Crocus'' (; plural: crocuses or croci) is a genus of seasonal flowering plants in the family Iridaceae (iris family) comprising about 100 species of perennials growing from corms. They are low growing plants, whose flower stems remain undergro ...

which originated in the Aegean basin, has left few material remains. According to Evans, the saffron (a sizable Minoan industry) was used for dye. Other archaeologists emphasize durable trade items: ceramics, copper, tin, gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

. The saffron may have had a religious significance. The saffron trade, which predated Minoan civilization, was comparable in value to that of frankincense

Frankincense (also known as olibanum) is an aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality incense').

There are several species o ...

or black pepper

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, known as a peppercorn, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diame ...

.

Costume

Sheep

Sheep wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

was the main fibre used in textiles, and perhaps a significant export commodity. Linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

from flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

was probably much less common, and possibly imported from Egypt, or grown locally. There is no evidence of silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

, but some use is possible.

As seen in Minoan art

Minoan art is the art produced by the Bronze Age Aegean Minoan civilization from about 3000 to 1100 BC, though the most extensive and finest survivals come from approximately 2300 to 1400 BC. It forms part of the wider grouping of Aegean art ...

, Minoan men wore loincloth

A loincloth is a one-piece garment, either wrapped around itself or kept in place by a belt. It covers the genitals and, at least partially, the buttocks. Loincloths which are held up by belts or strings are specifically known as breechcloth or ...

s (if poor) or robes or kilt

A kilt ( gd, fèileadh ; Irish: ''féileadh'') is a garment resembling a wrap-around knee-length skirt, made of twill woven worsted wool with heavy pleats at the sides and back and traditionally a tartan pattern. Originating in the Scottish Hi ...

s that were often long. Women wore long dresses with short sleeves and layered, flounced skirts. With both sexes, there was a great emphasis in art in a small wasp waist, often taken to improbable extremes. Both sexes are often shown with rather thick belts or girdles at the waist. Women could also wear a strapless, fitted bodice

A bodice () is an article of clothing traditionally for women and girls, covering the torso from the neck to the waist. The term typically refers to a specific type of upper garment common in Europe during the 16th to the 18th century, or to the ...

, and clothing patterns had symmetrical